Glymur Waterfall in Iceland: Complete Hiking Guide

Glymur is Iceland’s second-tallest waterfall (198 meters), but the height isn’t the main thing you’ll remember. What makes it amazing is the hike: you cross rivers, pass a small cave, and deal with a few narrow cliff sections before you get the big views. It’s doable, but it’s not a “show up in sneakers and wing it” kind of stop.

It also doesn’t feel like the waterfalls where you shuffle in, take the same photo as everyone else, and leave. You have to earn the lookouts here, and that changes the whole experience.

Key Takeaways

- Located in Hvalfjörður fjord, about 70km from Reykjavík (1–1.5 hour drive)

- 7km moderate-to-difficult hike with two river crossings and steep cliff sections

- Best visited June–September when the log bridge is installed, and conditions are safer

- Requires sturdy boots, trekking poles, and water shoes for river crossings

- No facilities at the trailhead, so bring everything you need

- Free parking but arrive early as the small lot fills up fast

Why Our Content Can Be Trusted

Lots of people share advice about Iceland, but what makes us different is that we’re a big team of locals who genuinely know and love this place. We grew up with the stories, the landscapes, and the quirky traditions, and we’ve spent our lives exploring everything from the famous sights to the hidden corners most visitors never hear about. We’re travelers too, so when we share tips, you can trust they’re real, accurate, and based on firsthand experience, not just copied from somewhere else.

What’s Glymur Waterfall? A Concise Overview

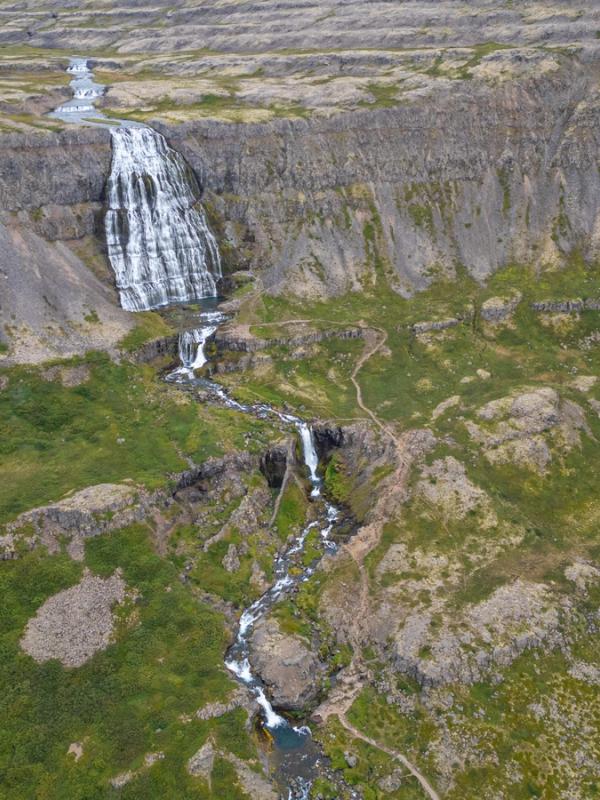

Glymur drops 198 meters into a narrow basalt canyon carved by the Botnsá River. The name comes from the Icelandic word “glymja,” meaning to echo or rumble, which makes sense the second you hear the water in that canyon.

It was considered Iceland’s tallest waterfall until 2011, when Morsárfoss was measured at 228 meters. Glymur is still much easier to reach, and the route is part of the point. The Botnsá River flows from Hvalvatn lake and spills over in a horsetail drop, with mossy cliffs that stay green because the mist is pretty much constant.

The geology is a big part of why it looks the way it does. Post-glacial meltwater carved through softer volcanic ash over 10,000 years, and the harder basalt above held together, creating a clean edge. That’s why the canyon feels so tight and steep.

Why Should I Visit Glymur Over Other Waterfalls in Iceland?

Mostly because you’re not in a crowd the whole time.

Skógafoss and Seljalandsfoss are easy to reach, which means they can get thousands of visitors a day. Getting to Glymur requires a proper hike, so the numbers drop fast. The 1998 Hvalfjörður Tunnel bypass also cut down on drive-by traffic, which helps keep it quieter.

And it’s a different kind of visit. Instead of standing at one platform, you get different angles as you climb up the canyon. You’ll go through a lava cave, cross a river (by log bridge when it’s installed), and wade through cold water. It’s a hike first, waterfall second.

There’s also the local legend: people say the canyon was carved by a cursed whale called Rauðhöfði (Red-Head), which thrashed its way up the river after being transformed from a man. Place names around the area, like Hvalklettur (Whale-Rock), still point back to that story.

If you want good photos without being boxed in by people, and you don’t mind working for the views, Glymur is worth the effort.

Location & How to Get There

Glymur is at the back of Hvalfjörður fjord in West Iceland. From Reykjavík, drive the Ring Road (Route 1) north for about 45 km, then turn right onto Route 47 just before the Hvalfjörður Tunnel. Follow Route 47 along the fjord for roughly 30 km. When you see the Glymur signs, turn onto a 3 km gravel access road that leads to the Botnsa parking area.

Total drive time is usually 60–70 minutes for about 72 km (44,5 miles). The paved roads are fine for any car. The last gravel section has potholes, but if you take it slow, it’s manageable. A 4x4 helps in wet conditions, but it’s not required on a normal summer day.

There’s no public transport to the trailhead, so you’ll need a rental vehicle or a guided tour from Reykjavík. Tours typically cost 15,000–20,000 ISK and include transport plus a guide for safety.

Parking is free, but the gravel lot is small (around 20–30 cars) and can fill up by 10 am on sunny summer days. If that happens, people end up parking along the access road. There are no facilities , no bathrooms, no snack stand, nothing, just an info board with the trail routes.

The Hiking to Glymur

You can’t reach Glymur without hiking. There’s no road, no quick viewpoint, and no shortcut.

The hike is about 6–7.5 km, depending on which route you choose, with 300–425 meters of elevation gain. Plan for 3–4 hours round-trip, and don’t be surprised if it turns into 5–6 hours with photo stops and breaks.

Trail Options:

- East-side out-and-back: The easier option and a good pick for beginners. You hike to the upper viewpoint and go back the same way.

- Full loop: More demanding, but you see the canyon from both sides and cross the river twice.

The Route Breakdown:

Start to Þvottahellir Cave (1 km, 20–30 minutes): Easy walking along the Botnsá River through birch scrub. Þvottahellir (“Washing Cave”) is a 50-meter lava tube you can crawl through or skip via a path above. Bring a headlamp if you want to explore inside.

First River Crossing (1–3 km, 45–60 minutes): From mid-June to early October, there’s a log bridge with an overhead cable for balance. Face upstream, hold the rope with both hands, and side-step across. If the log isn’t there, you’ll wade through swift, cold water that can be knee-to-thigh deep.

After the crossing, the trail climbs steeply along narrow ledges (about 30–50cm wide). Fixed chains help with the trickiest parts. The drop-offs can be over 100 meters, and there are no railings, so this isn’t a good trail for anyone with vertigo.

Upper Crossing and Canyon Rim (3–4 km, 45–60 minutes): You wade the upper Botnsá River (anywhere from ankle to waist deep), and it stays cold: around 4–6°C even in summer. Water shoes or going barefoot usually works better than boots here. The payoff is a clear view down the full 198-meter drop.

Descent (4–7 km, 45–60 minutes): The west-side route back is steeper and usually wetter than the east-side route, with more chain sections. Trekking poles help a lot, especially on the way down.

Essential Gear:

- Waterproof hiking boots with a good grip

- Trekking poles (don’t skip these)

- Water shoes or old sneakers for river crossings

- Layered clothing plus a waterproof shell

- 2 liters of water per person

- High-energy snacks

- Dry bag for electronics

- Offline map downloaded (AllTrails works well)

Things to Do There

If you’ve got time and the weather holds, there’s more to do here than just hike to the viewpoint and head back.

Photography and Viewpoints

From the canyon rim, you get the classic top-down view of the waterfall. Walk north along the rim for views toward the power plant, or south for distant Highlands views. Early morning (7–9 am) and late afternoon (6–8 pm usually give the best lighting and fewer visitors.

The colors are strong: green moss, black volcanic rock, and blue water. A polarizing filter helps with glare on the water, and you’ll want to keep your camera protected from mist near the falls.

Birdwatching

Arctic terns nest along the canyon walls and dive for fish in the pools below. You might spot sea eagles overhead, using the rising air currents from the canyon. Golden plovers, ravens, and different ducks also show up.

Bring binoculars and sit quietly at the rim for 10–15 minutes. Early morning tends to have the most bird activity, before tour groups arrive.

Extended Rim Walking

There are informal paths along the canyon edge for up to a kilometer in either direction. It’s an easy way to get away from other hikers. The ground is uneven volcanic rock and moss, so watch your footing.

Cave Exploration

Þvottahellir near the start is worth checking out with a headlamp. It’s about 50 meters long and 1–2 meters high; not overly tight, but it still feels adventurous. The cave walls show how lava flowed and cooled thousands of years ago.

Key Information for Visitors

This trail is straightforward if conditions are good and you’re prepared. If conditions are poor or you’re under-geared, it becomes risky quickly.

Weather & Best Time to Visit

Iceland’s weather changes quickly, and the canyon can make it feel even more unpredictable.

June through September is the best time to go. The log bridge is installed, water levels are lower, and you get 18–24 hours of daylight.

July and August are usually the most reliable months, with temperatures around 10–15°C and the lowest chance of trail closures. June can work, but check conditions carefully — late snow sometimes delays access. September has fewer crowds and autumn colors, but shorter days and more changeable weather.

Winter (October–May) is dangerous and not recommended. The log bridge is removed, river levels rise, trails get icy, and daylight drops to 4–5 hours in December. There have been multiple rescues and fatalities in winter conditions.

What to Bring

There’s nothing at the trailhead, so you need to show up with what you’ll use.

Clothing:

- Waterproof hiking boots (Gore-Tex or similar)

- Quick-dry hiking pants

- Moisture-wicking base layer

- Insulating fleece or down layer

- Waterproof/breathable shell jacket

- Warm hat and waterproof gloves

- Extra socks and underwear

Gear:

- Trekking poles (essential for balance and safety)

- Water shoes or old sneakers for river crossings

- Neoprene socks (optional but nice for warmth)

- Dry bag for valuables

- First aid kit with blister treatment

- Headlamp for the cave

- Snacks and 2L water per person

Navigation:

- Offline GPS app (AllTrails Pro recommended)

- Physical backup map if possible

- Portable phone charger

Safety

There are real hazards here. Some ledges are only 30–50cm wide, with 100+ meter drops and no railings. Chains help, but they’re not a guarantee.

River crossings are the biggest risk. The current flows at approximately 2–3 km/h, and the water remains at 4–6°C even in summer. If the log bridge isn’t in place, link arms with other hikers and cross diagonally downstream.

Critical safety tips:

- Check vedur.is and safetravel.is for weather and trail conditions

- Tell someone your expected return time

- Turn back if the weather deteriorates or you feel unsafe

- Emergency number: 112 (spotty cell coverage past the cave)

- Nearest hospital: Akranes, 20–30 minutes by helicopter

Who shouldn’t attempt this hike:

- Children under 10

- Anyone with vertigo or fear of heights

- Inexperienced hikers without proper gear

- Solo hikers in shoulder seasons

Top Places to Visit Nearby

Glymur is in a handy spot for adding a few West Iceland stops, or swapping plans if the weather doesn’t cooperate.

Hvammsvík Hot Springs (20 minutes)

Good for recovery after the hike. These geothermal infinity pools look out over Hvalfjörður fjord and are maintained at 38–41°C. Entry fee starts at 5,900 ISK and includes access to saunas and towels. Sunset times are popular in summer, so book ahead.

War and Peace Museum (20 minutes)

This museum covers Hvalfjörður’s role as a WWII Allied naval base. You’ll see U-boat artifacts, uniforms, and drone footage of the fjord’s military history. Entry is 2,500 ISK, and it’s open daily. It sits where thousands of Allied sailors were stationed from 1940 to 1945.

Hraunfossar & Barnafoss (1 hour and 15 minutes)

Two waterfalls with a very different look. Hraunfossar comes out of a 900-meter lava field like a line of springs, and Barnafoss rushes through tight rock formations. It’s easy to do with 1 km walking paths and free parking.

Settlement Centre in Borgarnes (50 minutes)

Interactive exhibits on Iceland’s settlement period with turf house replicas and multimedia displays. Entry is 3,700 ISK, and there’s a café serving traditional lamb stew. The focus is on Egil’s Saga and other medieval Icelandic literature.

Deildartunguhver Hot Spring (60 minutes)

Europe’s most voluminous geothermal spring, pumping out 180 liters per second of 97°C water. You can walk the boardwalks and view it for free. The nearby Krauma Spa costs 7,490 ISK and uses water from a spring in its pools.

Reykholt Historic Site (65 minutes)

The former estate of scholar Snorri Sturluson. It includes Iceland’s oldest hot pool (Snorralaug) and ruins of his home, where he wrote many Icelandic sagas. It’s free to visit and tied closely to Icelandic literary history.

Conclusion

Glymur is the kind of hike that feels satisfying because it asks something from you. It’s not just a quick stop: you plan a bit, carry the right gear, and pay attention to the exposed sections. In return, you get a waterfall view that doesn’t feel handed to you.

Between the geology, the folklore, and the fact that it stays relatively quiet compared to the drive-up waterfalls, it’s a standout. Just respect the conditions, come prepared, and save it for summer when the route is safest.